By: Izumi Hasegawa September 19, 2014

Music legend Quincy Jones produced the documentary film Keep On Keepin’ On about his teacher and friend, jazz legend Clark Terry, and also young jazz pianist Justin Kauflin. This is a very beautiful film. We can learn about not only music but also life and the beauty of friendship.

Quincy and Justin sat together with us and talked about their thoughts on music, mentors and friendship.

Q: My grandpa had a similar experience as Clark but I’m surprised Clark Terry still has the passion to make music after his legs were amputated. My grandpa didn’t have that will after his amputation. So I think music has power. What is the definition of music for you guys?

Q: My grandpa had a similar experience as Clark but I’m surprised Clark Terry still has the passion to make music after his legs were amputated. My grandpa didn’t have that will after his amputation. So I think music has power. What is the definition of music for you guys?

Quincy: It does have the power. It’s left and right brain. We tried to deny that it was connected with mathematics. But I went to the Berklee College of Music with Joseph Schillinger. Somehow, there is just this amazing relationship between mathematicians and musicians—the binary, trinary numbers. I didn’t want to admit it at first, because it sounded too mechanical to me. It’s not. There are as many tricks with mathematics as there are with music, you know. Mike Milken has taught me a lot of those. It’s amazing stuff.

Justin: You talk about music and how with Clark it’s a lifeline for him, it always brings him to life. He was always so passionate about music. He’s so dedicated. He has spent his whole life performing but also the act of teaching is something that also really has empowered him and given him new life.

Quincy: That’s happened to him later.

Quincy: That’s happened to him later.

Justin: Right. It’s been remarkable for us when we would visit him in the hospital. He might be tired or down before he knew his students were there. But then when we would show up he’d light up because it’s something that he’s so passionate about. He loves it so much that it really has been something that has invigorated him in the midst of all his health issues and struggles, and being that old.

Quincy: It goes along with God’s word: Love, laugh, live and give. It probably happened to him too because I remember he told me that at first he turned Miles (Davis) down (as a student) and he felt bad about it, because he taught me and then he went back to Miles, and all these years later, 60 years later, here he still is. A brother.

Q: What was the most important lesson you learned from Clark Terry?

Q: What was the most important lesson you learned from Clark Terry?

Justin: Obviously, if you’ve seen the film, there’s a lot of wisdom that he shares—just in the letter that he wrote and sent me, and the things that he tells me. But watching him, and how he’s been all his life, it’s selflessness. He was always selfless when it came to being a performer. That’s what made him such an amazing performer. He always was thinking about the people around him, whether it was the audience or the band he was playing with, and then into his teaching, how incredibly selfless he’s been with all of his students—from Quincy, all the way to me and my peers. He really does live for others and I think that’s something I hope to emulate in some way. Now that I have had the privilege of spending time with him, and with being connected with people like him and Quincy, it’s my responsibility to be able to share that with my generation and younger, because it needs to continue. So I hope that I can channel that selflessness in my own career as well. We’ll see how that goes.

Quincy: Mine (lesson) was a very simple trumpet technicality. I was 13 and I played the trumpet, but I always played from inside like this (demonstrates on his hands). If I hit anything about a C high note, my lip would bleed. We’d go down to the theater every day. Basie lost all of his money gambling; he was the worst gambler who ever lived. He had to give his big band up and he ended up with four horns: Serge Chaloff, Dick Wetmore, Buddy DeFranco and Clark Terry. They didn’t want to go to the East Coast but between Portland (Ore.) and Vancouver and Seattle, they were there all the time. We’d sit and talk about stuff. I told him, “My lips would bleed when I played like that,” and he said, “No, turkey, put it up here.” (Higher up on his lip.) The armature and the breathing all that stuff, nonstop. Like (Kauflin) says, it’s endless, the things that (Clark) teaches. You never know where it’s going to come from. His playing is full of joy and humor.

Q: What did you learn from each other?

Q: What did you learn from each other?

Quincy: It feels almost like something that connects everybody. There’s a kindred spirit no matter what the age difference is between him and Clark, you know, they have the same sense of humor. When they talk to each other, it’s the same lips are greasy stuff. There’s a connection there. Jazz has a spirit that’s frightening because it’s everywhere on the planet.

Justin: Quincy, talking about the spirit of music and jazz, he’s all-embracing. (He laughs.) You can see, just him talking, he embraces everything. I hope that I can get a little bit of that because it’s unbelievable. Everywhere he goes, he embraces it.

Quincy: The cultures. One of my biggest pet peeves is that America is the only country without a minister of culture. The culture is the music, the food and the language. You can see why Miles (Davis) and Sam Getz recorded in 1949 in Stockholm. It pulls the cultures together. The hell with an army. I’m sick of all that, you know. “I’m going to kill you.” Assad. And all that crap.

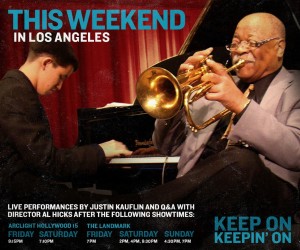

Keep On Keepin’ On opens in LA September 19th, and NY October 3rd.

There are special performances by Justin Kauflin plus a Q&A with the director, Al Hicks, at two theaters in Los Angeles. Details are below!